Author: Jason Brownlee

Weight regularization provides an approach to reduce the overfitting of a deep learning neural network model on the training data and improve the performance of the model on new data, such as the holdout test set.

There are multiple types of weight regularization, such as L1 and L2 vector norms, and each requires a hyperparameter that must be configured.

In this tutorial, you will discover how to apply weight regularization to improve the performance of an overfit deep learning neural network in Python with Keras.

After completing this tutorial, you will know:

- How to use the Keras API to add weight regularization to an MLP, CNN, or LSTM neural network.

- Examples of weight regularization configurations used in books and recent research papers.

- How to work through a case study for identifying an overfit model and improving test performance using weight regularization.

Let’s get started.

How to Reduce Overfitting in Deep Learning With Weight Regularization

Photo by Seabamirum, some rights reserved.

Tutorial Overview

This tutorial is divided into three parts; they are:

- Weight Regularization in Keras

- Examples of Weight Regularization

- Weight Regularization Case Study

Weight Regularization API in Keras

Keras provides a weight regularization API that allows you to add a penalty for weight size to the loss function.

Three different regularizer instances are provided; they are:

- L1: Sum of the absolute weights.

- L2: Sum of the squared weights.

- L1L2: Sum of the absolute and the squared weights.

The regularizers are provided under keras.regularizers and have the names l1, l2 and l1_l2. Each takes the regularizer hyperparameter as an argument. For example:

keras.regularizers.l1(0.01) keras.regularizers.l2(0.01) keras.regularizers.l1_l2(l1=0.01, l2=0.01)

By default, no regularizer is used in any layers.

A weight regularizer can be added to each layer when the layer is defined in a Keras model.

This is achieved by setting the kernel_regularizer argument on each layer. A separate regularizer can also be used for the bias via the bias_regularizer argument, although this is less often used.

Let’s look at some examples.

Weight Regularization for Dense Layers

The example below sets an l2 regularizer on a Dense fully connected layer:

# example of l2 on a dense layer from keras.layers import Dense from keras.regularizers import l2 ... model.add(Dense(32, kernel_regularizer=l2(0.01), bias_regularizer=l2(0.01))) ...

Weight Regularization for Convolutional Layers

Like the Dense layer, the Convolutional layers (e.g. Conv1D and Conv2D) also use the kernel_regularizer and bias_regularizer arguments to define a regularizer.

The example below sets an l2 regularizer on a Conv2D convolutional layer:

# example of l2 on a convolutional layer from keras.layers import Conv2D from keras.regularizers import l2 ... model.add(Conv2D(32, (3,3), kernel_regularizer=l2(0.01), bias_regularizer=l2(0.01))) ...

Weight Regularization for Recurrent Layers

Recurrent layers like the LSTM offer more flexibility in regularizing the weights.

The input, recurrent, and bias weights can all be regularized separately via the kernel_regularizer, recurrent_regularizer, and bias_regularizer arguments.

The example below sets an l2 regularizer on an LSTM recurrent layer:

# example of l2 on an lstm layer from keras.layers import LSTM from keras.regularizers import l2 ... model.add(LSTM(32, kernel_regularizer=l2(0.01), recurrent_regularizer=l2(0.01), bias_regularizer=l2(0.01))) ...

Examples of Weight Regularization

It can be helpful to look at some examples of weight regularization configurations reported in the literature.

It is important to select and tune a regularization technique specific to your network and dataset, although real examples can also give an idea of common configurations that may be a useful starting point.

Recall that 0.1 can be written in scientific notation as 1e-1 or 1E-1 or as an exponential 10^-1, 0.01 as 1e-2 or 10^-2 and so on.

Examples of MLP Weight Regularization

Weight regularization was borrowed from penalized regression models in statistics.

The most common type of regularization is L2, also called simply “weight decay,” with values often on a logarithmic scale between 0 and 0.1, such as 0.1, 0.001, 0.0001, etc.

Reasonable values of lambda [regularization hyperparameter] range between 0 and 0.1.

— Page 144, Applied Predictive Modeling, 2013.

The classic text on Multilayer Perceptrons “Neural Smithing: Supervised Learning in Feedforward Artificial Neural Networks” provides a worked example demonstrating the impact of weight decay by first training a model without any regularization, then steadily increasing the penalty. They demonstrate graphically that weight decay has the effect of improving the resulting decision function.

… net was trained […] with weight decay increasing from 0 to 1E-5 at 1200 epochs, to 1E-4 at 2500 epochs, and to 1E-3 at 400 epochs. […] The surface is smoother and transitions are more gradual

— Page 270, Neural Smithing: Supervised Learning in Feedforward Artificial Neural Networks, 1999.

This is an interesting procedure that may be worth investigating. The authors also comment on the difficulty of predicting the effect of weight decay on a problem.

… it is difficult to predict ahead of time what value is needed to achieve desired results. The value of 0.001 was chosen arbitrarily because it is a typically cited round number

— Page 270, Neural Smithing: Supervised Learning in Feedforward Artificial Neural Networks, 1999.

Examples of CNN Weight Regularization

Weight regularization does not seem widely used in CNN models, or if it is used, its use is not widely reported.

L2 weight regularization with very small regularization hyperparameters such as (e.g. 0.0005 or 5 x 10^−4) may be a good starting point.

Alex Krizhevsky, et al. from the University of Toronto in their 2012 paper titled “ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks” developed a deep CNN model for the ImageNet dataset, achieving then state-of-the-art results reported:

…and weight decay of 0.0005. We found that this small amount of weight decay was important for the model to learn. In other words, weight decay here is not merely a regularizer: it reduces the model’s training error.

Karen Simonyan and Andrew Zisserman from Oxford in their 2015 paper titled “Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition” develop a CNN for the ImageNet dataset and report:

The training was regularised by weight decay (the L2 penalty multiplier set to 5 x 10^−4)

Francois Chollet from Google (and author of Keras) in his 2016 paper titled “Xception: Deep Learning with Depthwise Separable Convolutions” reported the weight decay for both the Inception V3 CNN model from Google (not clear from the Inception V3 paper) and the weight decay used in his improved Xception for the ImageNet dataset:

The Inception V3 model uses a weight decay (L2 regularization) rate of 4e−5, which has been carefully tuned for performance on ImageNet. We found this rate to be quite suboptimal for Xception and instead settled for 1e−5.

Examples of LSTM Weight Regularization

It is common to use weight regularization with LSTM models.

An often used configuration is L2 (weight decay) and very small hyperparameters (e.g. 10^−6). It is often not reported what weights are regularized (input, recurrent, and/or bias), although one would assume that both input and recurrent weights are regularized only.

Gabriel Pereyra, et al. from Google Brain in the 2017 paper titled “Regularizing Neural Networks by Penalizing Confident Output Distributions” apply a seq2seq LSTMs models to predicting characters from the Wall Street Journal and report:

All models used weight decay of 10^−6

Barret Zoph and Quoc Le from Google Brain in the 2017 paper titled “Neural Architecture Search with Reinforcement Learning” use LSTMs and reinforcement learning to learn network architectures to best address the CIFAR-10 dataset and report:

weight decay of 1e-4

Ron Weiss, et al. from Google Brain and Nvidia in their 2017 paper titled “Sequence-to-Sequence Models Can Directly Translate Foreign Speech” develop a sequence-to-sequence LSTM for speech translation and report:

L2 weight decay is used with a weight of 10^−6

Weight Regularization Case Study

In this section, we will demonstrate how to use weight regularization to reduce overfitting of an MLP on a simple binary classification problem.

This example provides a template for applying weight regularization to your own neural network for classification and regression problems.

Binary Classification Problem

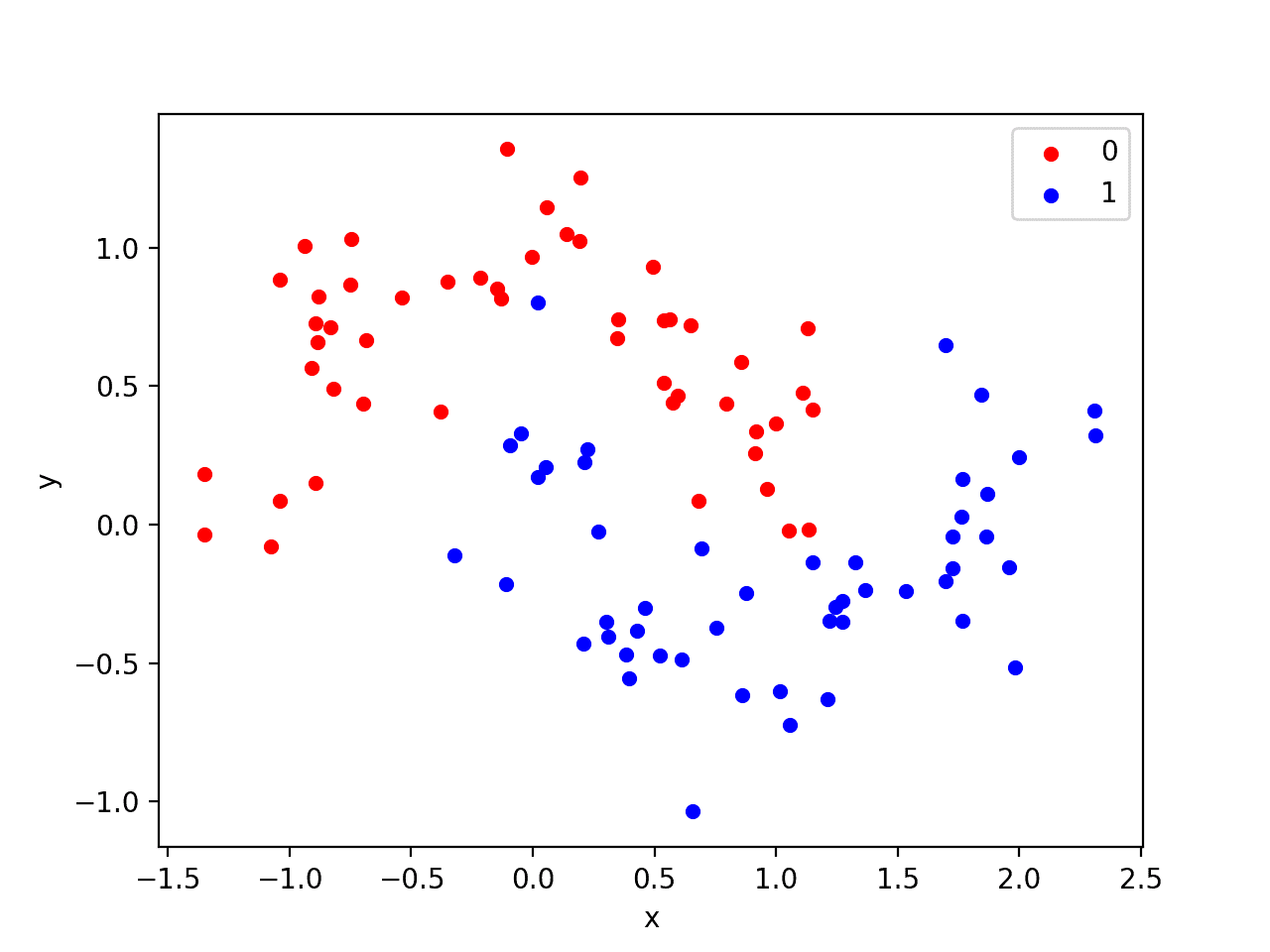

We will use a standard binary classification problem that defines two semi-circles of observations: one semi-circle for each class.

Each observation has two input variables with the same scale and a class output value of either 0 or 1. This dataset is called the “moons” dataset because of the shape of the observations in each class when plotted.

We can use the make_moons() function to generate observations from this problem. We will add noise to the data and seed the random number generator so that the same samples are generated each time the code is run.

# generate 2d classification dataset X, y = make_moons(n_samples=100, noise=0.2, random_state=1)

We can plot the dataset where the two variables are taken as x and y coordinates on a graph and the class value is taken as the color of the observation.

The complete example of generating the dataset and plotting it is listed below.

# generate two moons dataset

from sklearn.datasets import make_moons

from matplotlib import pyplot

from pandas import DataFrame

# generate 2d classification dataset

X, y = make_moons(n_samples=100, noise=0.2, random_state=1)

# scatter plot, dots colored by class value

df = DataFrame(dict(x=X[:,0], y=X[:,1], label=y))

colors = {0:'red', 1:'blue'}

fig, ax = pyplot.subplots()

grouped = df.groupby('label')

for key, group in grouped:

group.plot(ax=ax, kind='scatter', x='x', y='y', label=key, color=colors[key])

pyplot.show()

Running the example creates a scatter plot showing the semi-circle or moon shape of the observations in each class. We can see the noise in the dispersal of the points making the moons less obvious.

Scatter Plot of Moons Dataset With Color Showing the Class Value of Each Sample

This is a good test problem because the classes cannot be separated by a line, e.g. are not linearly separable, requiring a nonlinear method such as a neural network to address.

We have only generated 100 samples, which is small for a neural network, providing the opportunity to overfit the training dataset and have higher error on the test dataset: a good case for using regularization. Further, the samples have noise, giving the model an opportunity to learn aspects of the samples that don’t generalize.

Overfit Multilayer Perceptron Model

We can develop an MLP model to address this binary classification problem.

The model will have one hidden layer with more nodes that may be required to solve this problem, providing an opportunity to overfit. We will also train the model for longer than is required to ensure the model overfits.

Before we define the model, we will split the dataset into train and test sets, using 30 examples to train the model and 70 to evaluate the fit model’s performance.

# generate 2d classification dataset X, y = make_moons(n_samples=100, noise=0.2, random_state=1) # split into train and test n_train = 30 trainX, testX = X[:n_train, :], X[n_train:, :] trainy, testy = y[:n_train], y[n_train:]

Next, we can define the model.

The model uses 500 nodes in the hidden layer and the rectified linear activation function.

A sigmoid activation function is used in the output layer in order to predict class values of 0 or 1.

The model is optimized using the binary cross entropy loss function, suitable for binary classification problems and the efficient Adam version of gradient descent.

# define model model = Sequential() model.add(Dense(500, input_dim=2, activation='relu')) model.add(Dense(1, activation='sigmoid')) model.compile(loss='binary_crossentropy', optimizer='adam', metrics=['accuracy'])

The defined model is then fit on the training data for 4,000 epochs and the default batch size of 32.

# fit model model.fit(trainX, trainy, epochs=4000, verbose=0)

Finally, we can evaluate the performance of the model on the test dataset and report the result.

# evaluate the model

_, train_acc = model.evaluate(trainX, trainy, verbose=0)

_, test_acc = model.evaluate(testX, testy, verbose=0)

print('Train: %.3f, Test: %.3f' % (train_acc, test_acc))

We can tie all of these pieces together; the complete example is listed below.

# overfit mlp for the moons dataset

from sklearn.datasets import make_moons

from keras.layers import Dense

from keras.models import Sequential

# generate 2d classification dataset

X, y = make_moons(n_samples=100, noise=0.2, random_state=1)

# split into train and test

n_train = 30

trainX, testX = X[:n_train, :], X[n_train:, :]

trainy, testy = y[:n_train], y[n_train:]

# define model

model = Sequential()

model.add(Dense(500, input_dim=2, activation='relu'))

model.add(Dense(1, activation='sigmoid'))

model.compile(loss='binary_crossentropy', optimizer='adam', metrics=['accuracy'])

# fit model

model.fit(trainX, trainy, epochs=4000, verbose=0)

# evaluate the model

_, train_acc = model.evaluate(trainX, trainy, verbose=0)

_, test_acc = model.evaluate(testX, testy, verbose=0)

print('Train: %.3f, Test: %.3f' % (train_acc, test_acc))

Running the example reports the model performance on the train and test datasets.

We can see that the model has better performance on the training dataset than the test dataset, one possible sign of overfitting.

Your specific results may vary given the stochastic nature of the neural network and the training algorithm. Because the model is severely overfit, we generally would not expect much, if any, variance in the accuracy across repeated runs of the model on the same dataset.

Train: 1.000, Test: 0.914

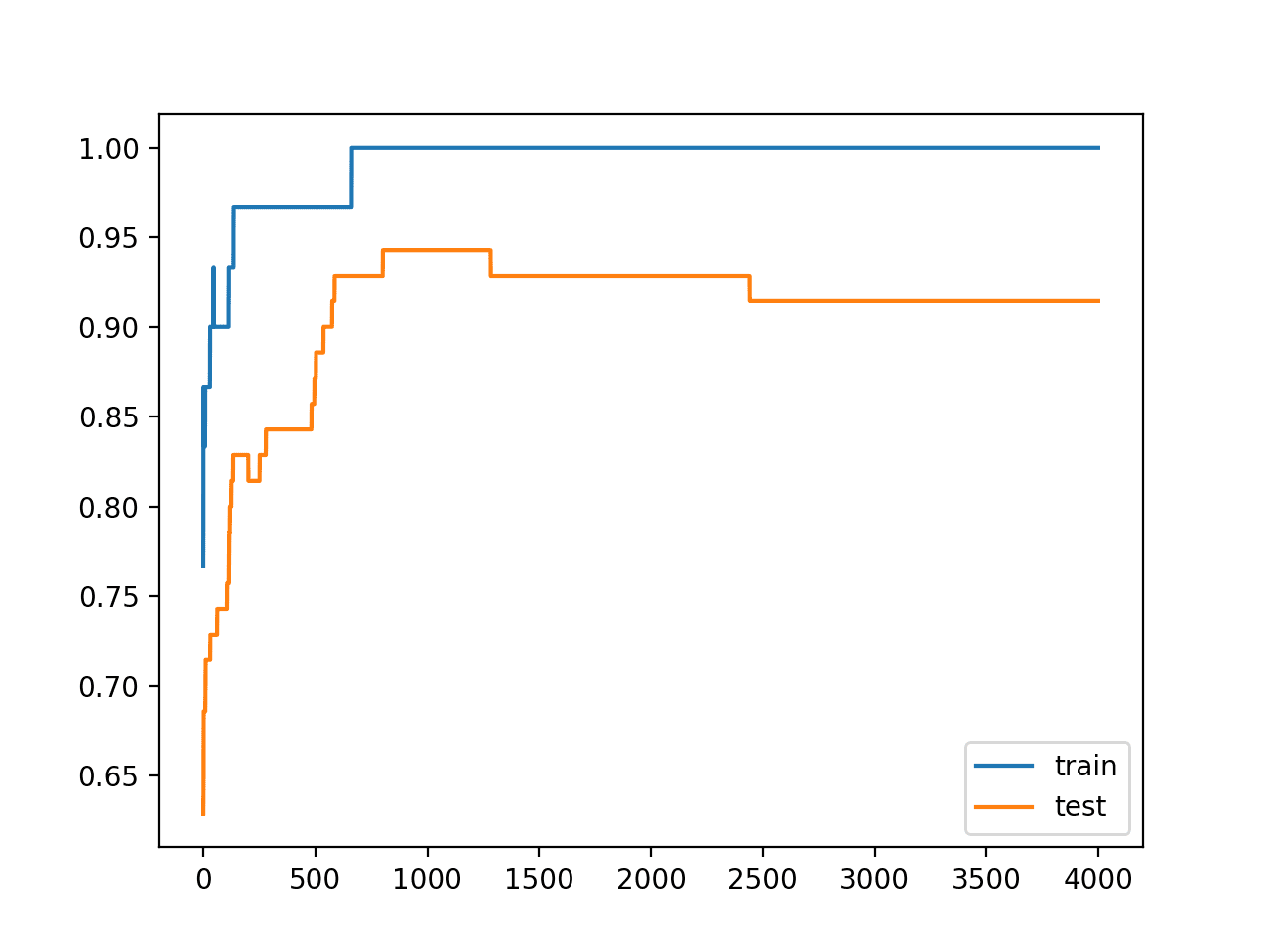

Another sign of overfitting is a plot of the learning curves of the model for both train and test datasets while training.

An overfit model should show accuracy increasing on both train and test and at some point accuracy drops on the test dataset but continues to rise on the test dataset.

We can update the example to plot these curves. The complete example is listed below.

# overfit mlp for the moons dataset plotting history from sklearn.datasets import make_moons from keras.layers import Dense from keras.models import Sequential from matplotlib import pyplot # generate 2d classification dataset X, y = make_moons(n_samples=100, noise=0.2, random_state=1) # split into train and test n_train = 30 trainX, testX = X[:n_train, :], X[n_train:, :] trainy, testy = y[:n_train], y[n_train:] # define model model = Sequential() model.add(Dense(500, input_dim=2, activation='relu')) model.add(Dense(1, activation='sigmoid')) model.compile(loss='binary_crossentropy', optimizer='adam', metrics=['accuracy']) # fit model history = model.fit(trainX, trainy, validation_data=(testX, testy), epochs=4000, verbose=0) # plot history # summarize history for accuracy pyplot.plot(history.history['acc'], label='train') pyplot.plot(history.history['val_acc'], label='test') pyplot.legend() pyplot.show()

Running the example creates line plots of the model accuracy on the train and test sets.

We can see an expected shape of an overfit model where test accuracy increases to a point and then begins to decrease again.

Line Plots of Accuracy on Train and Test Datasets While Training

MLP Model With Weight Regularization

We can add weight regularization to the hidden layer to reduce the overfitting of the model to the training dataset and improve the performance on the holdout set.

We will use the L2 vector norm also called weight decay with a regularization parameter (called alpha or lambda) of 0.001, chosen arbitrarily.

This can be done by adding the kernel_regularizer argument to the layer and setting it to an instance of l2.

model.add(Dense(500, input_dim=2, activation='relu', kernel_regularizer=l2(0.001)))

The updated example of fitting and evaluating the model on the moons dataset with weight regularization is listed below.

# mlp with weight regularization for the moons dataset

from sklearn.datasets import make_moons

from keras.layers import Dense

from keras.models import Sequential

from keras.regularizers import l2

# generate 2d classification dataset

X, y = make_moons(n_samples=100, noise=0.2, random_state=1)

# split into train and test

n_train = 30

trainX, testX = X[:n_train, :], X[n_train:, :]

trainy, testy = y[:n_train], y[n_train:]

# define model

model = Sequential()

model.add(Dense(500, input_dim=2, activation='relu', kernel_regularizer=l2(0.001)))

model.add(Dense(1, activation='sigmoid'))

model.compile(loss='binary_crossentropy', optimizer='adam', metrics=['accuracy'])

# fit model

model.fit(trainX, trainy, epochs=4000, verbose=0)

# evaluate the model

_, train_acc = model.evaluate(trainX, trainy, verbose=0)

_, test_acc = model.evaluate(testX, testy, verbose=0)

print('Train: %.3f, Test: %.3f' % (train_acc, test_acc))

Running the example reports the performance of the model on the train and test datasets.

We can see no change in the accuracy on the training dataset and an improvement on the test dataset.

Train: 1.000, Test: 0.943

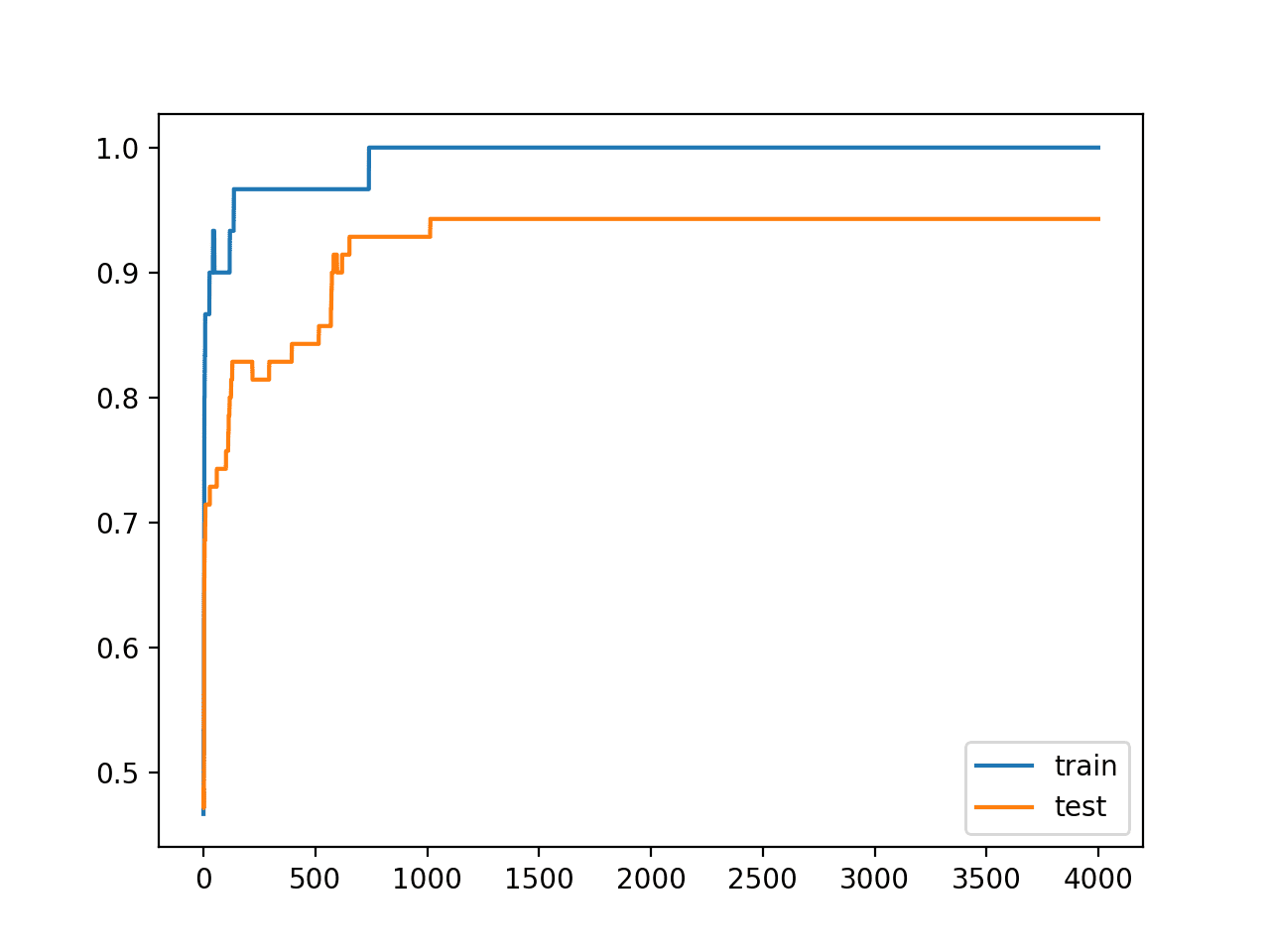

We would expect that the telltale learning curve for overfitting would also have been changed through the use of weight regularization.

Instead of the accuracy of the model on the test set increasing and then decreasing again, we should see it continually rise during training.

The complete example of fitting the model and plotting the train and test learning curves is listed below.

# mlp with weight regularization for the moons dataset plotting history from sklearn.datasets import make_moons from keras.layers import Dense from keras.models import Sequential from keras.regularizers import l2 from matplotlib import pyplot # generate 2d classification dataset X, y = make_moons(n_samples=100, noise=0.2, random_state=1) # split into train and test n_train = 30 trainX, testX = X[:n_train, :], X[n_train:, :] trainy, testy = y[:n_train], y[n_train:] # define model model = Sequential() model.add(Dense(500, input_dim=2, activation='relu', kernel_regularizer=l2(0.001))) model.add(Dense(1, activation='sigmoid')) model.compile(loss='binary_crossentropy', optimizer='adam', metrics=['accuracy']) # fit model history = model.fit(trainX, trainy, validation_data=(testX, testy), epochs=4000, verbose=0) # plot history # summarize history for accuracy pyplot.plot(history.history['acc'], label='train') pyplot.plot(history.history['val_acc'], label='test') pyplot.legend() pyplot.show()

Running the example creates line plots of the train and test accuracy for the model for each epoch during training.

As expected, we see the learning curve on the test dataset rise and then plateau, indicating that the model may not have overfit the training dataset.

Line Plots of Accuracy on Train and Test Datasets While Training Without Overfitting

Grid Search Regularization Hyperparameter

Once you can confirm that weight regularization may improve your overfit model, you can test different values of the regularization parameter.

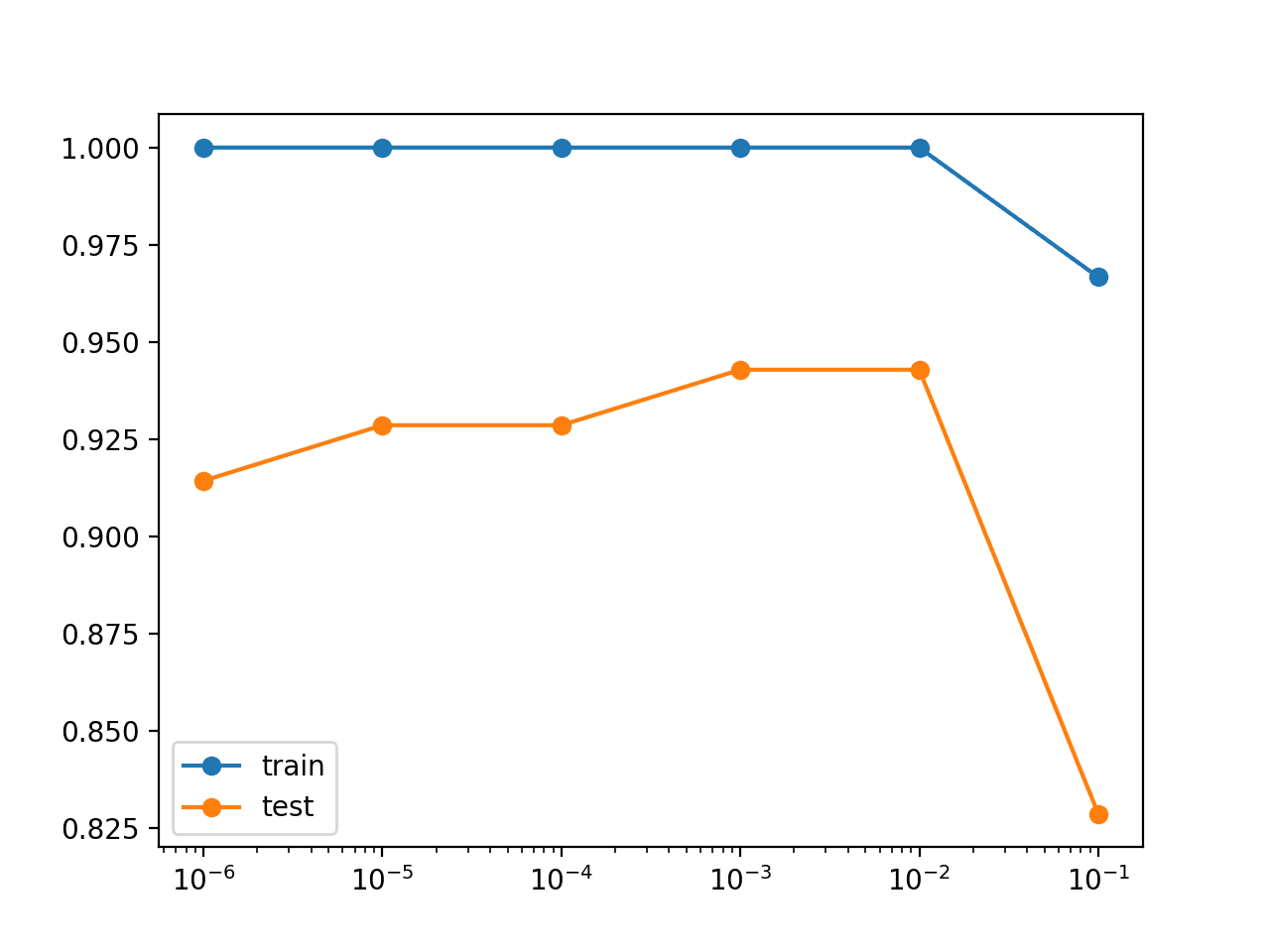

It is a good practice to first grid search through some orders of magnitude between 0.0 and 0.1, then once a level is found, to grid search on that level.

We can grid search through the orders of magnitude by defining the values to test, looping through each and recording the train and test performance.

... # grid search values values = [1e-1, 1e-2, 1e-3, 1e-4, 1e-5, 1e-6] all_train, all_test = list(), list() for param in values: ... model.add(Dense(500, input_dim=2, activation='relu', kernel_regularizer=l2(param))) ... all_train.append(train_acc) all_test.append(test_acc)

Once we have all of the values, we can graph the results as a line plot to help spot any patterns in the configurations to the train and test accuracies.

Because parameters jump orders of magnitude (powers of 10), we can create a line plot of the results using a logarithmic scale. The Matplotlib library allows this via the semilogx() function. For example:

pyplot.semilogx(values, all_train, label='train', marker='o') pyplot.semilogx(values, all_test, label='test', marker='o')

The complete example for grid searching weight regularization values on the moon dataset is listed below.

# grid search regularization values for moons dataset

from sklearn.datasets import make_moons

from keras.layers import Dense

from keras.models import Sequential

from keras.regularizers import l2

from matplotlib import pyplot

# generate 2d classification dataset

X, y = make_moons(n_samples=100, noise=0.2, random_state=1)

# split into train and test

n_train = 30

trainX, testX = X[:n_train, :], X[n_train:, :]

trainy, testy = y[:n_train], y[n_train:]

# grid search values

values = [1e-1, 1e-2, 1e-3, 1e-4, 1e-5, 1e-6]

all_train, all_test = list(), list()

for param in values:

# define model

model = Sequential()

model.add(Dense(500, input_dim=2, activation='relu', kernel_regularizer=l2(param)))

model.add(Dense(1, activation='sigmoid'))

model.compile(loss='binary_crossentropy', optimizer='adam', metrics=['accuracy'])

# fit model

model.fit(trainX, trainy, epochs=4000, verbose=0)

# evaluate the model

_, train_acc = model.evaluate(trainX, trainy, verbose=0)

_, test_acc = model.evaluate(testX, testy, verbose=0)

print('Param: %f, Train: %.3f, Test: %.3f' % (param, train_acc, test_acc))

all_train.append(train_acc)

all_test.append(test_acc)

# plot train and test means

pyplot.semilogx(values, all_train, label='train', marker='o')

pyplot.semilogx(values, all_test, label='test', marker='o')

pyplot.legend()

pyplot.show()

Running the example prints the parameter value and the accuracy on the train and test sets for each evaluated model.

The results suggest that 0.01 or 0.001 may be sufficient and may provide good bounds for further grid searching.

Param: 0.100000, Train: 0.967, Test: 0.829 Param: 0.010000, Train: 1.000, Test: 0.943 Param: 0.001000, Train: 1.000, Test: 0.943 Param: 0.000100, Train: 1.000, Test: 0.929 Param: 0.000010, Train: 1.000, Test: 0.929 Param: 0.000001, Train: 1.000, Test: 0.914

A line plot of the results is also created, showing the increase in test accuracy with larger weight regularization parameter values, at least to a point.

We can see that using the largest value of 0.1 results in a large drop in both train and test accuracy.

Line Plot of Model Accuracy on Train and Test Datasets With Different Weight Regularization Parameters

Extensions

This section lists some ideas for extending the tutorial that you may wish to explore.

- Try Alternates. Update the example to use L1 or the combined L1L2 methods instead of L2 regularization.

- Report Weight Norm. Update the example to calculate the magnitude of the network weights and demonstrate that regularization indeed made the magnitude smaller.

- Regularize Output Layer. Update the example to regularize the output layer of the model and compare the results.

- Regularize Bias. Update the example to regularize the bias weight and compare the results.

- Repeated Model Evaluation. Update the example to fit and evaluate the model multiple times and report the mean and standard deviation of model performance.

- Grid Search Along Order of Magnitude. Update the grid search example to grid search within the best-performing order of magnitude of parameter values.

- Repeated Regularization of Model. Create a new example to continue the training of a fit model with increasing levels of regularization (e.g. 1E-6, 1E-5, etc.) and see if it results in a better performing model on the test set.

If you explore any of these extensions, I’d love to know.

Further Reading

This section provides more resources on the topic if you are looking to go deeper.

Posts

- How to Use Weight Regularization with LSTM Networks for Time Series Forecasting

- Gentle Introduction to Vector Norms in Machine Learning

API

- Keras Regularization API

- Keras Core Layers API

- Keras Convolutional Layers API

- Keras Recurrent Layers API

- sklearn.datasets.make_moons API

- matplotlib.pyplot.semilogx API

Summary

In this tutorial, you discovered how to apply weight regularization to improve the performance of an overfit deep learning neural network in Python with Keras.

Specifically, you learned:

- How to use Keras API to add weight regularization to an MLP, CNN, or LSTM neural network.

- Examples of weight regularization configurations used in books and recent research papers.

- How to work through a case study for identifying an overfit model and improving test performance using weight regularization.

Do you have any questions?

Ask your questions in the comments below and I will do my best to answer.

The post How to Reduce Overfitting of a Deep Learning Model with Weight Regularization appeared first on Machine Learning Mastery.